Inspired by a friend of mine who just started his computer science career at CMU out of high school, I have finally found some time to write this long waited Undergraduate Research 101 to help more young and bright students to get to the right track to becoming future researchers. Normally when you see a blog post like this, it is written from the perspective of the faculty members but this time I would like to give away my five cents to my peers who are eager to get involved with cutting-edge technology from a student’s perspective.

Similar to my other blog posts, I would like to structure the article into the answers to the following questions, the reason I do this is that I believe having a question to think about while reading something engages oneself more as compared to purely passive knowledge intake by glimpsing through lines of text:

- What is research?

- Is research for me?

- When should I start?

- How should I start?

What is research?

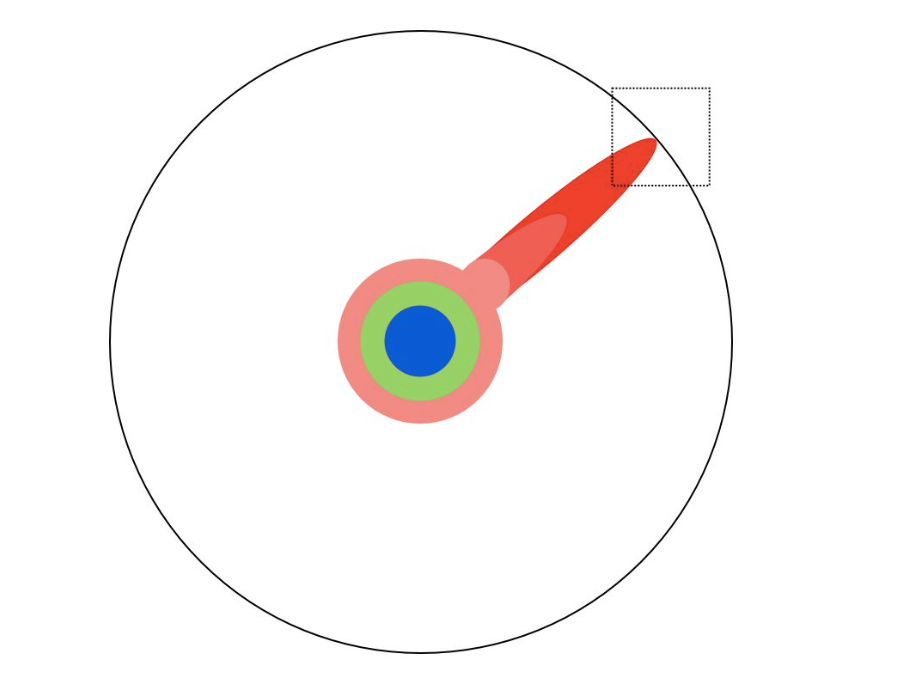

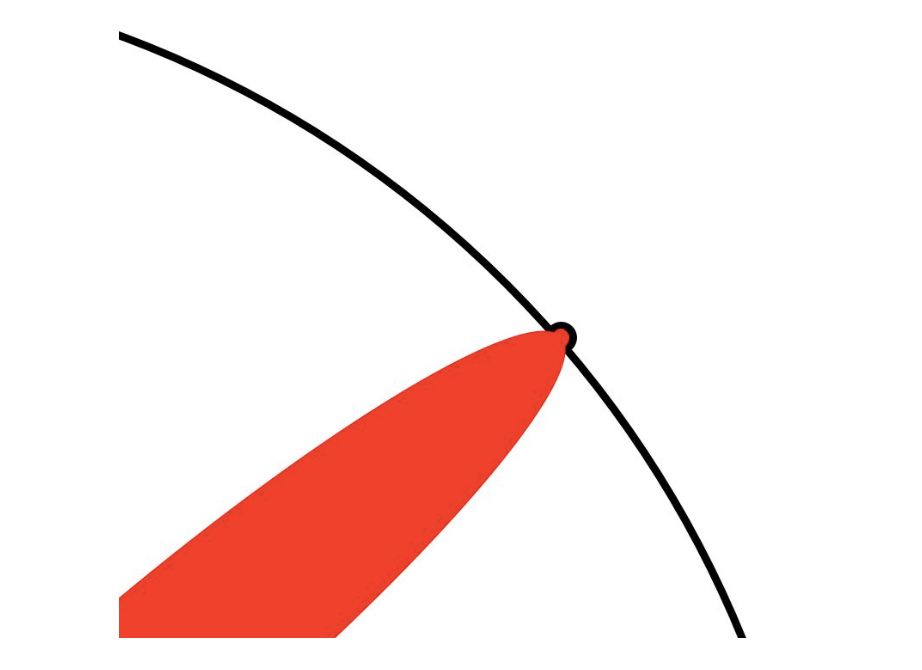

For this, I would highly encourage you to read about The illustrated guide to a Ph.D. written by Matt Might who is a professor of computer science at University of Utah. In figure I, Might invites us to think of the knowledge that we obtain after the completion of different school levels as circles. As we climb up the academia ladder, the circle that we leave behind will grow bigger and bigger and there exists this outer loop called human knowledge boundary as shown in figure II. The purpose of research is to try to make a bump out of that boundary at a narrow scope.

Figure I

Figure I

Figure II

Figure II

From having a well-rounded education background to be able to do something that no one else has done before takes years of commitment, and yet starting from you undergraduate years will help you reach the outer layer faster. However as interesting as research might be, you need to know your priorities well when things get tough. Without a doubt, doing well in coursework deserves to be on the top of the list if not the most important one. The rationale is simple. Even if you are excited about how to build driveless cars or develop the next-generation super computers, you need to have solid fundaments in math, computer science and even writing so that you will be able to understand other people’s work and implement a new algorithm that you just came up with to see if it really works or not. Of course paying attention to courses in other disciplines might help you develop soft skills for future collaboration.

Meanwhile, you need to understand doing research is different from taking classes. Doing well in class is important but it is by no means the ticket to become the next Albert Einstein for they require different kinds of skill sets. Conducting research often needs you to be creative in ways that no one else has ever been and work independently when your research question leaves out lots of uncertainty for you to figure out whereas taking classes require you to comprehend the concepts that have been fairly well studied and working on the problem sets under clear requirements.

My sincere suggestion on course work is trying to do reasonably well in them and spend the rest of your time on other things that are also important such as research, sports, friends and family.

Is research for me?

Really the best way to find out is to try to find a professor in your university and work with him/her for a semester or two. If you are not sure if you even want to get started, you ask yourself a few questions to determine whether you will enjoy research or not.

- Are you OK with working independently?

- Are you OK with working on something of which the requirements are largely unspecified and you will have to find them out yourself?

- Are you OK with getting stuck on something and you may not be able to find the solution until two weeks/months later?

- Are you OK with not being able to find the answers on Google and still not freak out : )

If all of your answers are yes or maybe yes, then I think you can give it a try. Otherwise, you would probably want to take more classes and explore different things before you dive into research.

When should I start?

I would say it is never too early to start. I started working with professor Kohlhase at Jacobs University towards the end of the first semester in college on Semantic Tex(sTex) and at that time I didn’t even know how to do git properly. Even if you don’t that is OK. You can still learn those things on the fly as long as you are motivated.

For students who are from large research universities like CMU, it is easier to find world-class researchers who need people in their labs, but for those who aren’t in similar situations, you are not completely hopeless, there might still be opportunities in the neighboring institutes and maybe spending the summer at some good labs will also be a good choice.

Regardless how much you have learned when you first enter college, by working in a research group even on some of the very trivial problems will help you gain a better perspective about the field that you are interested in and you will be able to appreciate more about what you study in lectures. For an example, I had formal language and logic (FLL) in my second year. FLL was a theory course which first introduced formal languages and many people were not motivated and lost interests when going through the tedious proofs. On the contrary, I had more incentives to do well because for the research that I was involved in used the knowledge of formal languages. It was the OMdoc and OpenMath schemata that I needed to look into which properly specified the the markups for mathematics. I knew the reasons behind studying the different kinds of languages and grammars and I was applying those knowledge into the real world already.

It really feels like reading a very long paper. You first want to read the title, the abstract, the table of content to gain a broad view of that the paper is about and you start with the introduction and the conclusion to make sure if you want to go into any details of the paper and then proceed with the sections of your interests. Doing early research is like do the initial steps, helping you know what is going to happen in the end and then you reading the paper chapter by chapter to build up the knowledge needed for reaching the conclusion. When you are in this process, being aware of the main objective will reduce the chances of you getting lost and help you stay focused on the important bits.

How should I start?

If you want to take things slowly, I think the easiest way is to take classes from different areas and go to the seminars and reading groups of that topic if you find interested. Maybe after a while you have a better idea what the field is about and might be able to identify some problems that you want to solve then you can start to approach the professor that teaches that class and then things get rolling.

If you already vaguely know what interests you when entering college like my friend that I mentioned in the very beginning this post, then you can already start emailing professors to see if they have any openings for undergraduates especially the first year students. There are many things you need to know before you actually take action. The most basics include how to write an email properly. The professors aren’t like high school teachers. They are really busy. You want to try extra hard to make their life easier such that you are more likely to get a response.

- How to email professor and Virtually Guarantee the Response

- How to send and reply to email

- How to Email Your Professor (without being annoying AF)

Most generally, you might get frustrated if you don’t any a reply from the professor who you want to work with, send a follow up email a week after if you still haven’t heard back. Your email might just disappear in the sea of letters. The key here is really about the quality but not the quantity.

When you send an email to a professor to ask for a research assistant position, you first would want to read the professor’s website thoroughly because most of the time you can find almost everything you need. Some professors put a secrete code on their websites just to filter out the students who simply spam hundreds of faculty members at the same time. There are some other professors will simply say they won’t take any undergraduate at the moment so you don’t have to waste your time sending an email.

Summer is also a great time to do research, and what I found helpful was doing lab rotations. Even in the same institute you will find the group atmosphere differs and even if you already have a great supervisor already like the one I have, you will still appreciate the time you spend in other labs. Only via the lab rotation which exposes you to different things can you identify what you really like and what you don’t. It is impossible to know what the working environment is like until you are physically there being part of the group. Also, research is not a one man battle, but a collaborative effort, as a future researcher, you will for sure need to deal with people from different disciplines and countries, and the summer research experience will give you an edge over your peers for sure. Here I have a list of excellent undergraduate research programs that you can look into:

- Caltech Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowships

- MIT Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program

- (German) Research Internships in Science and Engineering

- Amgen Scholars

Lastly, I want to share some excellent blogs and articles that I have been following that teach me things that I wouldn’t learn in a normal classroom setting:

- Matt Right: the person who wrote the Illustrated Guide to a Ph.D..

- Philip J. Guo: a blog of an assistant professor of cognitive science at UCSD. His The Ph.D. Grind can give you invaluable insights.

- David Andersen: maintained by an assistant professor of of computer science at CMU where he shares his thoughts on various topics.

- So long, and thanks for the Ph.D.!: a legacy guide that shall be read by all novice graduate students.

- Applying to Ph.D. Programs in Computer Science: written by our beloved Mor at CMU. You can tell her passion and energy in this writing.

- A Survival Guide to a Ph.d.: written by Andrej Karpahthy who is a Stanford graduate student. In this article he talks about his Ph.d. experiences.

- Ph.d. Comics: the must have for all!

I didn’t know what I was supposed to do either when I was still a freshman and there were times when I thought about why I was doing all of these. When things like this happen, make sure you have a strong support system that you can rely on. The support system can include your supervisors, graduate students in your research group, friends, family and even your college consulting center. Seek for their help. Some of them might have been in the similar situation before, so they will be able to share your sentiments and probably propose some plausible solutions and the others might have no idea of what you are experiencing, but they will at least give you mental support. Again I can’t emphasize this more, doing research or anything in life is not a one man task. You will be in much better position if you know who to ask, when to ask and how to ask help. These are the skills that you don’t learn overnight but pick up as you advance in your career.

Last words

The friend who pushed me to finally write this blog is Phillip Wang. We met on the first night that I arrived at CMU and I was looking for where to pick up the keys to my dorm. He was still a college freshman in the orientation week but he offered me help, seeing me looking for directions with my luggage in hand. It turned out we became good friends and I have been always impressed by his curiosity and the ability to comprehend abstract concepts that people of his age have difficulty understanding. I hope Phill will benefit from reading this and at least learn how to write a proper email instead of just using hi to address the professors : ) and of course I hope other students also have a clearer idea of how to get started with undergraduate research.