Thinking is perhaps the most important and yet most under-valued activity for young scientists. When I went through my PhD training, I saw myself and other highly motivated peers being mostly occupied with activities of doing science rather than thinking.

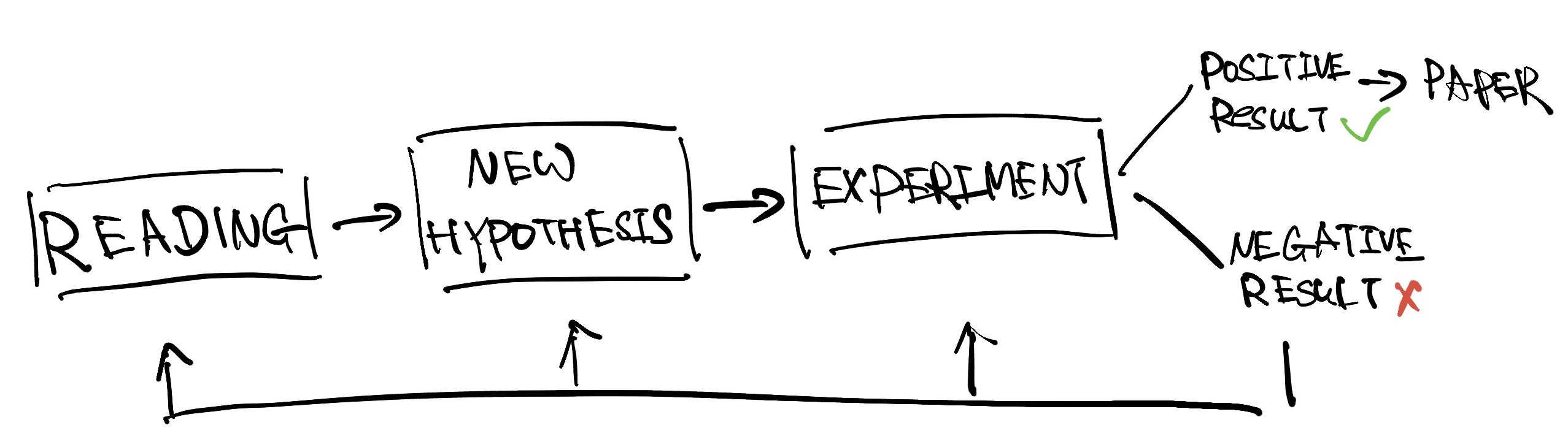

PhD students spend most of their time doing science for good and bad reasons. As trainees, we should learn essential skills that will enable us to do science. Nonetheless, PhD students are often stuck in a cycle of grinding out papers without time for deep thinking. As PhD students, we start a project by reading some papers, forming a new hypothesis and conducting an experiment to test our hypothesis. When an idea works, we write up the results and publish a paper (Figure 1). When an idea fails, we go back to any of the previous steps depending on how much belief we have in the idea itself. The less belief we have, the further up we move in the discovery progress. In a PhD program, we repeat the same loop until we have about 2-3 papers over 3+ years in Europe and 5+ years in the US. By the end of this journey, we bundle up all the results and massage the text to make up a more coherent story for the thesis.

Thinking as an activity is not built into our workflow because whenever we think. Even though we do spend time thinking when choosing our PhD project and writing our thesis, we will be considered as unproductive in today’s competitive scientific envrionment.

Thinking in sciences can happen at different layers of abstraction. The day-to-day scientific investigation, domain-specific thinking, and thinking in the context of the history of science:

- Day-to-day: thinking related to how to make experiments happen, interpreate the results and refine the hypotheses on a daily basis

- Domain-specific: how the work done is relevant in the broader context of a discipline in recent development

- History of science: how the work contributs to the history of science in one or several disciplines over a longer period (10+ years)

Young scientists spend most of their time thinking about their day-to-day investigations and less time on the relevance of the work in domain-specific content. Very little time is spent on thinking about the history of science. I’d argue that thinking at a higher level of abstraction is hugely valuable.

Due to the lack of domain-specific thinking, most of my machine learning PhD friends left academia because no one will use the novel methods they propose in the real world. They are right because the datasets used in machine learning research are not reflective of the real world. If their models were developed and tested on easier data, why would we expect them to be equally effective outside academia? If the lack of real-world impact is what they value, early in their PhD, they could have first thought about the properties of machine learning problems that have real-world impact, identified the resources they need to work on those problems, and then chose the problems that they have the highest chance of solving. With sufficient thinking early in the PhD training, many such limitations can be addressed. Our schools excel at teaching the students how to solve problems but much less so in choosing which questions to ask. Learning which questions to ask requires deep thinking and is a much harder skill to teach as it is open-ended.

Many scientists are frustrated by negative results precisely because they have not thought enough about the history of science. The currency in academia is publications. Because of how academia is structured, the chances of getting published are significantly higher if we find positive results. However, most investigations will not produce positive results. The key is to see success through failure, which wouldn’t be possible without thinking about the history of science.

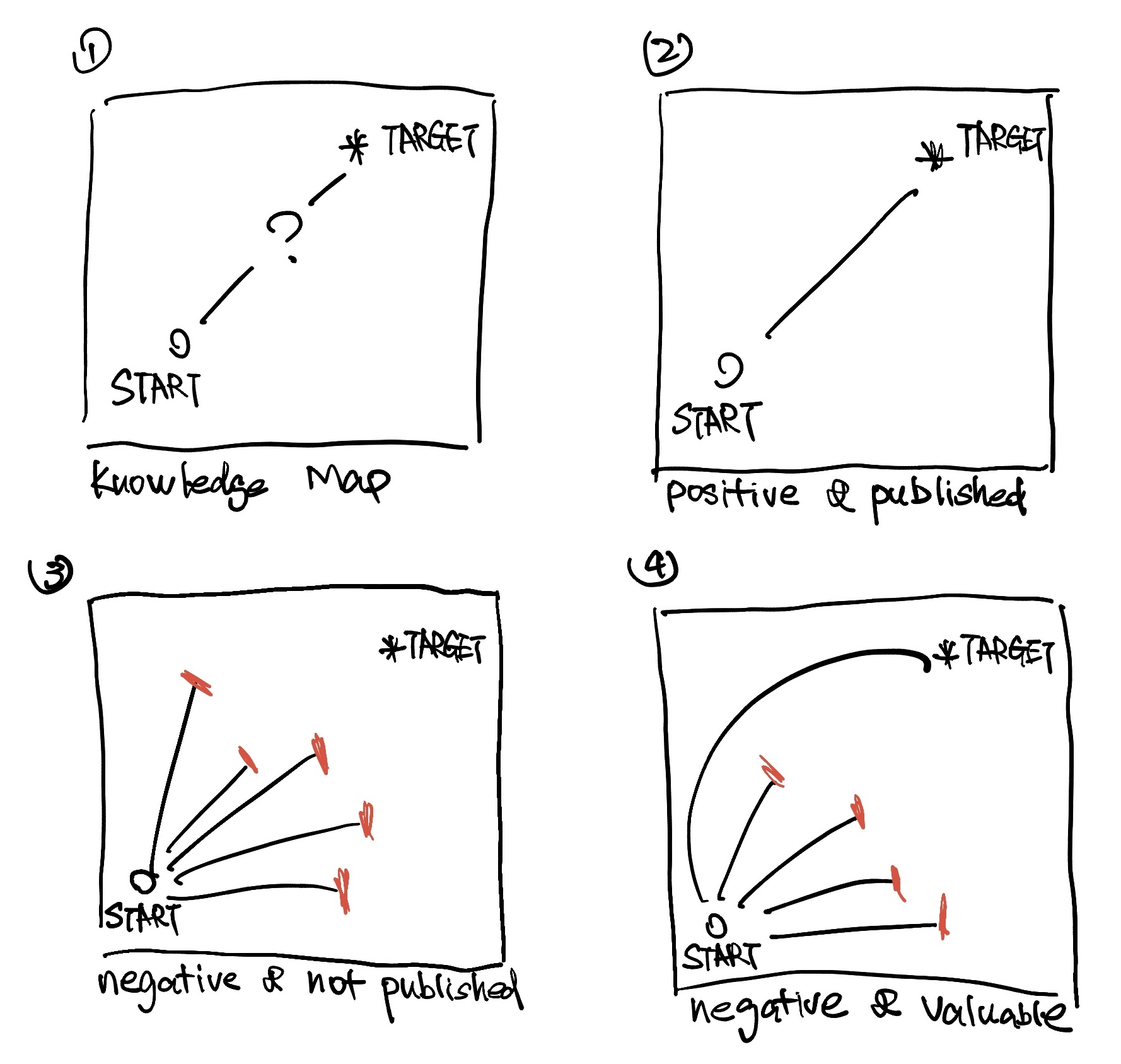

A good mental model is to consider the accumulation of scientific processes akin to drawing a map of knowledge (Figure 2). For a novel problem, we start with some known facts and then explore different ways of solving this problem (Figure 2.1). In rare circumstances, the first solution we try can address the novel problem, making it relatively easy to get published (Figure 2.2). However, most of the time, we are running in circles, facing dead ends for several years (Figure 2.3). Sadly, negative results are often not published, putting people’s careers on hold. A key point that goes unnoticed is that the negative results can be equally valuable as scientific knowledge. Science is not just about how we solve every problem out there. Science is also about identifying why certain solutions work whilst others don’t. But it takes someone who understands the history of science, aka how science progresses, to appreciate both the positive and negative results. Most of the time, things don’t go the way that we want, but we just need to put trust into the process by filling out the map of knowledge step by step.

Doing science is hard, but thinking about science is harder because it is a less well-taught skill. I know some people like to think in a solitary fashion. For me, at least, I enjoy discussing ideas with my colleagues and, at times, writing down my own thinking to help articulate my thoughts. Every scientist should deliberately spend time thinking on their own and strive to get better at it; otherwise, we might risk thinking superficially, simply reacting to the information we receive. I fear that will be the death of our scientific creativity.